12 November, 2019

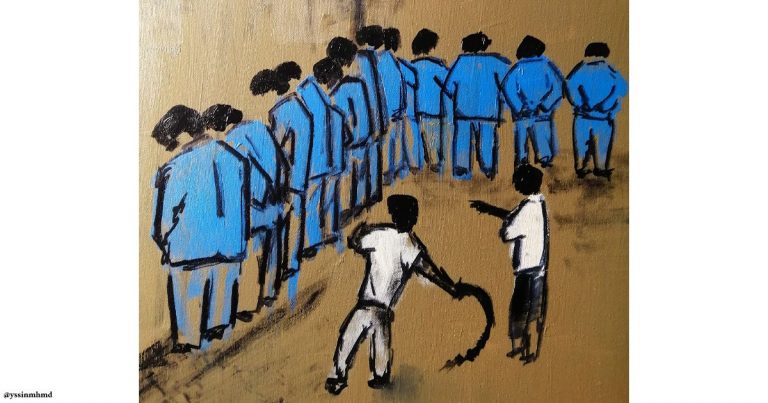

Egypt: Systematic torture is a state policy

Joint UN submission by rights groups exposes endemic torture and appalling conditions in Egypt’s prisons

Harrowing testimonies of systematic torture continue being too frequently heard as the date for Egypt’s Universal Periodic Review (UPR) approaches; Egypt’s review will take place on the 13th of November 09-12.30 Geneva Time. Allegations of torture have spiked especially in connection to the wave of arrests following demonstrations in late September (more than 4000 were arrested during less than one week). The cases of torture inflicted on, and testified by, rights lawyer Mohamed al-Baqer, blogger and activist Alaa Abdel Fattah, and journalist Esraa Abdel Fattah are but only a small fraction of the many verified testimonies detailing torture and cruel treatment over the last five years.[1]

Not only do the Egyptian authorities use torture to extract false confessions from persons forcibly disappeared in unofficial detention sites; they have also expanded the use of torture in formal detention sites, particularly against political opponents, as detailed in a joint report on torture submitted to the UPR last March by Egyptian and international rights organizations.[2] From 2014 to the end of 2018, 449 prisoners died in places of detention, 85 of them as a result of torture, as documented by the report. These numbers don’t include those who died from intentional medical neglect and an often prolonged denial of vital healthcare, a regular practice in Egyptian prisons that is critically threatening the life of former presidential candidate Dr. Abdel Moneim Aboul-Fotouh, the head of the opposition party Strong Egypt, who has been detained since February 2018. Medical neglect also caused the death of former President Mohamed Morsi in June.

Given the widespread and systematic use of torture reported, it is unavoidable to assume that the highest levels of the Egypt government have greenlighted such practice, while at the same time shielding perpetrators from accountability, particularly when torture victims are political dissidents. In other words, torture is no longer a crime falling under individual culpability, but rather, it has become a state policy with the objective of deterring –by instilling fear – citizens’ participation in the public sphere. This is evidenced by recent amendments in legislation, in particular to the Counterterrorism Law, which made it legal to detain people for 14 days—later amended to 28—before bringing them before the investigative agencies; thereby lengthening the timespan under which there is no formal accountability for any crimes committed against detainees typically held in incommunicado in undisclosed locations. At the same time, the state has failed to adhere to its pledges to redefine the crime of torture in line with the Egyptian constitution and the Convention Against Torture—in fact, it has prosecuted rights activists who have sought to do so.

Alongside Egypt’s legislative system, Egypt’s judicial system enables systematic torture. The Public Prosecution, particularly the High State Security Prosecution, colludes in covering up torture and protecting perpetrators. The joint report on torture documents cases in which defendants reported torture to the prosecutor, and the prosecutor ignored or failed to investigate the allegations.[3] Courts disregard defendants’ allegations of torture used to extract confessions; and sentence to defendants to prison or even to death on the basis of confessions coerced under torture. In this respect, the report’s findings are similar to those of with the United Nations’ Report of the Committee Against Torture:

“Torture appears to occur particularly frequently following arbitrary arrests and is often carried out to obtain a confession or to punish and threaten political dissenters. Torture occurs in police stations, prisons, State security facilities, and Central Security Forces facilities. Torture is perpetrated by police officers, military officers, National Security officers and prison guards. However, prosecutors, judges and prison officials also facilitate torture by failing to curb practices of torture, arbitrary detention and ill-treatment or to act on complaints. Many documented incidents occurred in greater Cairo, but cases have also been reported throughout the country. Perpetrators of torture almost universally enjoy impunity, although Egyptian law prohibits and creates accountability mechanisms for torture and related practices, demonstrating a serious dissonance between law and practice. In the view of the Committee, all the above lead to the inescapable conclusion that torture is a systematic practice in Egypt.”

The rampant proliferation of torture and its transformation into state policy has normalized the crime in Egypt; altering victims’ perceptions of its severity. Many no longer consider kicking, slapping, threats, and psychological harm to be torture; only electroshocks, whipping, or brutal assault or violence causing substantial harm or major disability are considered torture.

In this context, the report addresses the numerous types of torture inflicted upon detainees, particularly persons charged in political cases. These include enforced disappearance and incommunicado detention, and filmed confessions coerced by torture, duress or threat, which are then used as propaganda films produced by the military or Interior Ministry.[4]

Egypt’s upcoming UPR may be the final opportunity to implement the report’s recommendations to counteract torture. These include pressuring the Egyptian government to allow UN experts—particularly the UN special rapporteur on torture and the special rapporteur on counterterrorism and human rights—to visit Egypt, as well as to permit the International Committee of the Red Cross and relevant national and international NGOs to visit and inspect detention sites. The Egyptian government should also create a national preventive mechanism composed of independent rights organizations authorized to make unannounced visits to detention sites to ensure that torture is not being practiced.

At the same time, the UN and the international community should pressure Egypt to ratify the Optional Protocol to the UN Convention Against Torture and join the International Convention on the Protection of All Persons from Enforced Disappearance.

[1] Some of those who have given statements refuse to reveal their identities in fear of reprisals that could bring additional torture or more severe detention conditions.

[2] The NGOs are: Committee for Justice, Cairo Institute for Human Rights Studies (CIHRS), DIGNITY – Danish Institute Against Torture, El Nadeem Center for the Rehabilitation of Victims of Violence (El Nadeem), Egyptian Commission for Rights and Freedoms – Europe (ECRF – Europe). And due to reprisals and threats faced by human rights defenders on a daily basis in Egypt, Another NGO contributing to this report opted to remain anonymous. The group is henceforth referred as the Coalition.

[3] At best, persons alleging torture are referred to a forensic examiner long after their torture to ensure that no physical traces remain

[4] One of many examples is the recent one of a group of students and foreign tourists arrested in central Cairo. Egyptian media aired videos of them confessing under duress to taking part in an international conspiracy to foment chaos in Egypt. The falsity of these claims was proven days later, and they were released and allowed to return to their home countries.